The [Neo]Colonial Gaze

Tourism and Urban Identity Projection in Kolkata

Alexandra Sanyal (MDes Critical Conservation ‘20)

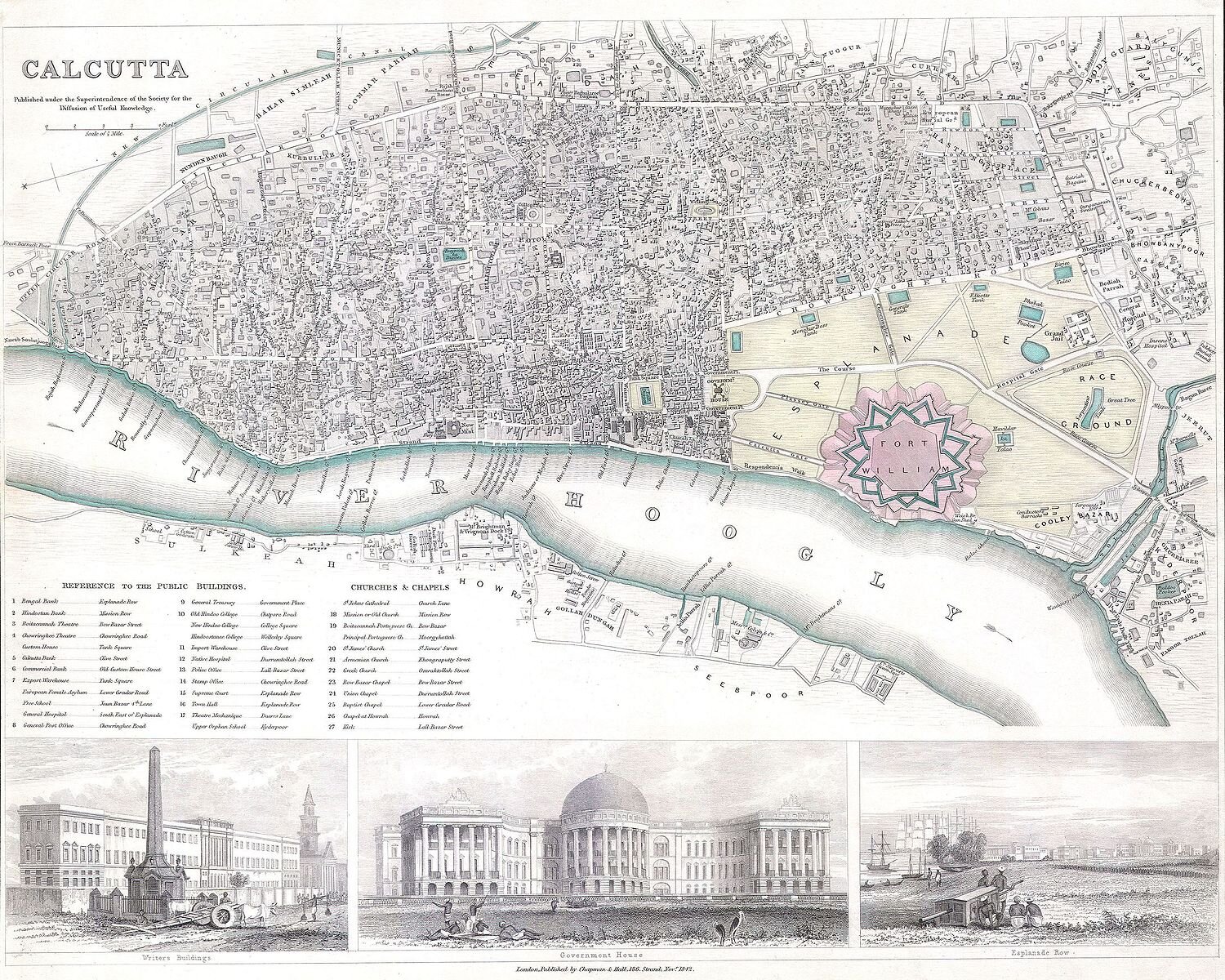

Maps of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Vol 1. 1844.

The imperial gaze and its power over global understandings of colonized societies was perhaps one of the most subtly abusive components of the colonial project. The colonizer used observation and representation to craft and distribute an understanding of the “orient” that solidified the already widespread hegemonic notions of “the West and the rest.” These observations, and the explorers that conducted them, embodied a moral power that normalized a representation of the East that has endured, indefinitely shaping our understanding of the colonized.

For more than two centuries, Kolkata was the power center of the colonized Indian nation; its history is virtually inseparable from colonialism. Originating from the fusion of three villages and becoming a fortified trading post at the hands of the British, Kolkata is now India’s third largest city. Since its establishment, Kolkata has been a popular destination for foreign visitors, making tourism a major benefactor of Kolkata’s economy and livelihood.

After comparing materials from colonial and “postcolonial” Kolkata, I found that much of the hegemony of vision remains. Earlier materials were constructed and disseminated using methodologies such as stereographs, which established distance between the viewer and the viewed. This separated them into different worlds and power structures, as per the desire of travelers who wanted to “know” a place without seeing its totality. Contemporary materials are equally focused on what is considered “appealing” (according to Western standards) for potential visitors, censoring descriptions to fit expectations. This reductive technique affects where, when, and how visitors see Kolkata by extending a narrow urban narrative: identifying Kolkata as eternally colonial.

At its core, tourism is an embodiment of a constant search for authenticity; a process through which we consume a social experience of place. Tourism enables a sense of false consciousness by mystifying the visitor into believing that they are privileged to experience someplace new and “real.” However, what is manipulated to look real is often staged, set up to feed a specific reading to the tourist. Thus, the more we rely on those experiences to tell simplified and commodified stories of place, the less justice we do. Additionally, tourism enables certain self-interested local constituencies to deploy modified historical memories, indoctrinating the tourist with a constructed narrative of place which, over time, becomes branded. In the case of Kolkata, the tourist gaze so impacts the socio-spatial fabric of the city that tourists determine the city’s growth. This makes it extremely difficult for Kolkata to self-identify as anything more than [colonial] heritage to be consumed. But, for whom in Kolkata does the tourism industry speak? Who is included and excluded in the narrative?

In my work, I question the extent to which the city’s identity, and the mechanisms through which it is projected, such as tourism, has changed in the context of “postcoloniality,” and what this reveals about the power conflicts and narratives that govern the city today. The postcolonial process is much more than just governmental liberation; it has to do with reimagined representations of identity and an appreciation for a history that goes beyond that imposed by imperial powers. It is those processes that are so complicated, and thus so critical, for cities like Kolkata, formed under the colonial project with little recognized pre-colonial history. I fear that if we continue to read binary narratives of “imperial versus indigenous” or “pre versus postcolonial” history, we will lose the complexity and hybridity of Bengali culture, architecture, and society. The nuance of Bengali identity is found in this fusion, creating a need for new methods of analysis that go beyond “postcolonial” theory as it currently stands.

[1] De Beaufort, E.P. 1845. The Calcutta Star Almanac: A Stranger’s Guide in Calcutta.

[2] Department of Tourism Website. “West Bengal (Kolkata).” https://wbtourismgov.in/home/kolkata

[3] Lonely Planet. “Kolkata.” https://www.lonelyplanet.com/india/kolkata-calcutta#experiences

[4] Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press.

[5] Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 1992. Postcoloniality and the Artifice of History: Who Speaks for "Indian" Pasts?. Author(s): University of California Press. Representations, No. 37.

[6] D’Eramo, Marco. 2004. UNESCOCIDE. The New Left Review 88.

[7] Edney, Matthew. 2001. Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[8] Herzfeld, Michael. 2006. Spatial Cleansing: Monumental Vacuity and Idea of the West. Journal of Material Culture, Vol. 11(½).

[9] MacCannell, Dean. 1973. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 79, No.3.

[10] N.K. Sinha & Swapna Banerjee-Guha. 2018. Calcutta. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. https://www.britannica.com/place/Kolkata